Engineered to Protect People and Budgets

Fewer steps, fewer trades, and higher structural performance

Construction is fragmented too many materials, too many trades, too much risk

Every layer adds complexity, cost, and opportunity for failure

One System

Seven Solutions

Zero Compromise

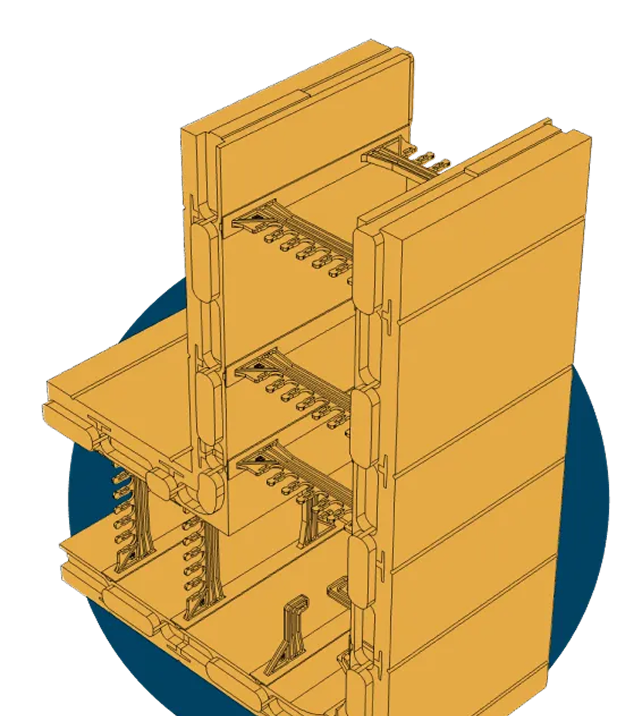

Monolith integrates seven critical layers of performance into one continuous wall system — eliminating weak points and simplifyingevery build

Monolith 7-in-1 Building System

Seven building layers combined into one continuous pour — designed for performance that lasts.

Reinforced concrete core forms the backbone of every wall

R-65+ performance when combined with thermal mass

Non-combustible with a 3+-hour burn time — will not melt or ignite

Closed-cell polyurethane locks out moisture.

Airtight design prevents energy loss and condensation

STC 55+ acoustic rating delivers quiet, comfortable spaces

Non-reactive fastening grid supports direct finishing — no extra framing

Monolith 7-in-1 Building System

Seven building layers combined into one continuous pour — designed for performance that lasts.

Reinforced concrete core forms the backbone of every wall

R-65+ performance when combined with thermal mass

Non-combustible with a 3+-hour burn time — will not melt or ignite.

Closed-cell polyurethane locks out moisture.

Airtight design prevents energy loss and condensation.

STC 55+ acoustic rating delivers quiet, comfortable spaces.

“In a similar climate where my homes average $200 a month for heating and cooling, our Monolith home costs around $25.”

— Homeowner, North Dakota Build (2024)

Engineered for Every Project — Above or Below Grade

From homes to high-rises, Monolith adapts to every build and elevates performance in ways traditional materials can’t

Monolith turns luxury homes into true luxury fortresses — delivering unmatched comfort, silence, safety, and long-term durability that elevate both the experience of living and the value of the property.

With R-65+ effective insulation and airtight wall performance, Monolith maintains flawless indoor comfort across every room and every season. The home feels consistently warm or cool with minimal HVAC use — a premium-level energy experience that becomes immediately noticeable to discerning buyers.

The reinforced concrete core and non-combustible polyurethane form add inherent protection from fire, impact, moisture, and extreme weather, delivering a level of structural security that traditional framing simply cannot match.

Acoustic excellence is another hallmark of a true luxury build. With STC 55+ sound performance, Monolith creates whisper-quiet interiors — ideal for luxury estates, home theaters, and spaces where privacy and serenity are non-negotiable.

Finish-ready surfaces preserve architectural precision by eliminating warping, settling, or movement over time. This protects clean lines, premium finishes, and the long-term integrity of high-end craftsmanship.

Together, these advantages create a home that is not only stronger and quieter, but also valued up to 5% higher on resale — a premium driven by performance, security, and operating efficiency that luxury buyers actively seek.

Monolith doesn’t just build luxury homes — it builds luxury fortresses that endure.

Monolith accelerates schedules, reduces trade coordination, and delivers long-term operating savings — making multifamily and workforce housing faster to build and more economical to own.

With a reinforced concrete core and integrated 7-in-1 performance layers, Monolith replaces multiple trades and materials with one streamlined system. Crews can build straighter, cleaner walls in less time, reducing delays and improving consistency across large unit counts.

The system provides exceptional sound control (STC 55+), dramatically improving tenant comfort in high-density buildings and reducing noise complaints — one of the top drivers of turnover in multifamily housing.

R-65+ effective insulation and airtight construction lower heating and cooling demand across all units, reducing operational expenses and helping property owners achieve higher energy ratings and better performance under emerging building codes.

The non-combustible, fire-resistant wall assembly enhances life safety and simplifies code compliance, while the moisture- and pest-resistant form prevents long-term maintenance issues common in wood-framed structures.

Combined with finish-ready surfaces that reduce interior labor, Monolith helps developers deliver more durable, efficient, and quiet homes — improving tenant satisfaction and lowering lifetime ownership costs for both workforce and market-rate housing.

Monolith strengthens commercial and mixed-use buildings with a unified wall system that accelerates schedules, reduces lifecycle costs, and delivers long-term structural performance far beyond code minimums.

By integrating structure, insulation, fire resistance, and finish-ready surfaces into a single system, Monolith eliminates multiple subcontractors and material layers. This simplifies coordination on complex sites, keeps schedules predictable, and reduces the risk of delays caused by trade overlap or weather exposure.

The reinforced concrete core and non-combustible polyurethane form provide superior fire separation and impact resistance — critical for buildings with shared walls, public-facing areas, ground-floor retail, or mixed occupancy requirements. This inherent performance supports smoother approvals and helps meet stringent safety codes without additional materials.

With R-65+ effective insulation and airtight design, commercial tenants benefit from significantly lower energy consumption and a more stable indoor environment. Reduced HVAC loads and fewer thermal bridges contribute to sustainable building certifications and lower operating costs over the life of the asset.

The system’s STC 55+ sound isolation improves acoustics in offices, shared walls, hospitality suites, and mixed-use spaces, enhancing tenant comfort and reducing noise complaints — a major factor in commercial leasing satisfaction.

Combined with finish-ready surfaces that speed up interior build-outs, Monolith allows developers to deliver stronger, more efficient, and lower-maintenance buildings that maintain their value and performance long after traditional construction begins to degrade.

Monolith gives public buildings a stronger, safer, and more durable foundation — protecting people and budgets while reducing long-term maintenance burdens for cities and institutions.

With a reinforced concrete core and non-combustible, Class 1/A fire-resistant form, Monolith delivers inherent life-safety performance that exceeds the expectations for schools, municipal buildings, fire stations, emergency response centers, and other civic infrastructure.

The system integrates structure, insulation, air and vapor control, and sound performance into a single engineered wall — reducing the number of subcontractors involved and eliminating critical points of failure that plague conventional construction. This simplification lowers coordination risk, shortens schedules, and ensures a more predictable build for public projects where delays carry high financial and political costs.

With R-65+ effective insulation and airtight construction, Monolith reduces operational energy use year-round, contributing to lower taxpayer-funded utility costs and helping agencies meet modern energy code and sustainability requirements.

The system’s STC 55+ acoustics improve learning environments, administrative spaces, and public facilities by reducing outside noise, mechanical noise, and room-to-room sound transfer — a critical benefit for schools, medical buildings, and public safety centers.

Monolith is also naturally resistant to moisture, pests, and long-term material degradation, resulting in fewer repairs and reduced lifecycle expenses. Public buildings stay structurally sound and operationally efficient for generations — aligning with the responsibility cities have to protect their communities and their budgets

Monolith gives DIY builders a professional-grade wall system that’s easy to learn, simple to assemble, and engineered to deliver flawless results without specialized crews.

Each block is lightweight, interlocking, and designed to stack cleanly — allowing one or two people to build straight, accurate walls without heavy equipment or complex tools. Monolith eliminates multiple steps found in traditional construction by combining structure, insulation, air sealing, vapor control, and fastening into a single form system that’s intuitive to use.

DIYers appreciate that the system doesn’t warp, twist, or react to moisture, so walls stay true from the first course to the final pour. The finish-ready surface eliminates the need for framing, furring strips, and extra layers, saving both time and budget on interior work.

With R-65+ thermal performance, non-combustible fire protection, and a reinforced concrete core, Monolith delivers a level of safety, efficiency, and durability that typically requires a professional crew to achieve — making high-performance construction accessible to homeowners and independent builders.

Whether building an addition, an outbuilding, or a full home, DIYers gain a system that installs quickly, performs for decades, and helps them build with confidence.

Monolith creates basements that stay dry, healthy, and thermally stable—without extra waterproofing layers or complicated finishing steps.

The closed-cell polyurethane form and reinforced concrete core are naturally resistant to moisture intrusion, mold growth, and rot. Unlike wood or EPS ICF, Monolith does not absorb water or degrade below grade, making it an ideal solution for long-term durability.

With an effective R-65+ thermal performance, basements maintain consistent temperatures and eliminate the cold, damp feel common in traditionally built lower levels.

The non-reactive, finish-ready surface means you can attach drywall or other finishes directly to the fastening grid—without furring strips, vapor barriers, or additional waterproofing membranes. This dramatically reduces finishing time and cost while still meeting below-grade building requirements.

The result is a basement that installs faster, costs less to finish, and performs for decades with minimal maintenance.

Monolith creates straighter, stronger, and more dimensionally stable pool walls — giving installers a predictable substrate that doesn’t bow, shift, or absorb moisture during construction.

The closed-cell polyurethane exterior prevents water, chlorine, and salts from penetrating and cycling into the concrete core. This significantly reduces the long-term chemical intrusion and degradation that modern concrete is vulnerable to, especially as mixes are produced with reduced fly ash and other supplementary cementitious materials. By keeping the concrete dry and chemically stable, Monolith helps prevent cracking, internal expansion, and long-term structural breakdown.

Installers benefit from fast, lightweight assembly, precise wall alignment, and a form system that maintains geometry under excavation and backfill loads — creating a more reliable base for professional waterproofing, tile, plaster, or membrane systems.

The added insulation helps maintain water temperature and reduce energy loss, but the core advantage is a pool wall system that installs faster, stays straighter, and protects the concrete core from the moisture and chemical cycles that shorten the lifespan of traditional pool structures.

Monolith delivers a level of protection that meets and exceeds the demands of safe rooms and storm shelters — with reinforced walls engineered to stand firm when everything else fails.

The system’s concrete core and rigid polyurethane form create a non-combustible, impact-resistant wall assembly that performs under extreme conditions. Monolith walls withstand wind forces exceeding 250 mph and resist debris impact, giving families and communities reliable shelter during tornadoes, hurricanes, and severe storms.

Unlike framed structures, Monolith does not rely on multiple layers or vulnerable fasteners. The integrated 7-in-1 design eliminates weak points by combining structure, insulation, air sealing, and fire protection in a single, continuous wall. This increases structural continuity and reduces the risk of failure under pressure, rotation, or uplift.

The closed-cell polyurethane exterior prevents moisture absorption and long-term material degradation — critical for safe rooms built within basements, garages, or below-grade areas that experience humidity shifts or groundwater pressure.

With natural fire resistance, airtight construction, and finish-ready surfaces, Monolith creates safe rooms that aren’t just strong — they’re secure, comfortable, and built to preserve life in the harshest conditions.

Whether incorporated into a home, school, community building, or emergency operations center, Monolith provides a predictable, high-performance system that protects people when it matters most.

What Builders Are Saying

Real-world simplicity. Proven performance.

“I’ve worked with Insulated Concrete Forms for many years, and the moment I picked up the Monolith block, I could tell it was different. The rigidity alone gave me confidence it would hold up during the pour.

Communication was great throughout the project, and the team even came on-site to assist when needed, which helped keep everything on track.

Solid product, solid support — and we plan to use Monolith on future projects.”

— Brent W

General Contractor, Utah

Recognized by the Industry That Builds Smarter

Hear how Monolith is reshaping construction — from theexperts who build and the voices who lea

Podcast Feature — Build with ICF Podcast

Featuring Monolith founder [Name] discussing the future of Polyurethane ICF and how Monolith redefines wall performance

YouTube Review — AI3 Powered by ICF Guru

Independent product review highlighting Monolith’s 7-in-1 system, burn test, and on-site installation speed

Build to Withstand any Environment

Monolith is engineered for every region’s challenge

Wildfire

Flood

Seismic

Extreme

Built the Right Way to Protect People and Budgets.

Connect with a Monolith Specialist to plan your project, or share your floor plan toreceive a custom estimate

Downloadable Resource

Company Presentation

Introduce others to Monolith with a ready-to-share presentation deck

Spec Sheet

System dimensions, material data, andperformance testing — everything you needfor specification

MSRP Pricing

Reference pricing for standard blocks tohelp estimate project costs

Additional Resources

We're Here to Answer All Your Questions

Everything that you need to know about monolith. Cant find your answer here, talk to our amazing support team.

ICF is chosen over traditional construction methods because it delivers far better performance in energy efficiency, comfort, durability, and safety — with fewer long-term costs.

Traditional wood framing has multiple weak points: thermal bridging, moisture vulnerability, fire risk, noise transfer, and long-term material degradation. Even highly insulated wood walls often underperform because they rely on multiple layers and subcontractors, creating inconsistency from one section of the wall to another.

ICF solves these problems by combining a reinforced concrete core with continuous insulation on both sides. This creates a wall that:

• Eliminates thermal bridging for dramatically lower energy bills

• Blocks moisture and pests, preventing rot, mold, and long-term decay

• Delivers a quiet interior environment, reducing noise by 40–60%

• Resists fire, providing life-safety protection wood cannot match

• Withstands extreme weather far beyond code minimums

• Lasts for generations, not just decades

Because the structure is solid concrete, ICF homes stay stronger, straighter, and more comfortable — with fewer repairs and significantly lower heating and cooling costs. Builders also benefit from faster construction, simpler inspections, and more predictable jobsite schedules.

Overall, ICF offers the best combination of energy performance, safety, and building longevity — qualities traditional methods struggle to deliver consistently.

Monolith costs more upfront than wood framing and many EPS ICF systems — but significantly less over the life of the building, and often far less than trying to upgrade traditional construction to the same performance level.

Upfront Costs

• Materials cost more than wood framing

• Labor typically costs less due to fewer trades and faster assembly

• Integrated layers (structure, insulation, air barrier, vapor barrier, fire resistance) reduce additional material purchases

During Construction

• Fewer subcontractors = fewer delays, fewer change orders, and less coordination risk

• Straighter walls and integrated fastening lower interior finishing costs

Long-Term Value

• Energy savings of 50–80% dramatically reduce monthly bills

• No rot, mold, or pest-related repairs

• Far fewer long-term maintenance demands

• Built-in disaster resilience minimizes major repair risk

• Longer lifespan increases asset value and resale confidence

• Insurance savings may apply depending on region

The Critical Cost Reality

To bring a traditional wood-framed wall anywhere close to the performance of a polyurethane ICF wall, you must add continuous exterior insulation, advanced sheathing, air and vapor barriers, fire-rated assemblies, sound control layers, and far higher-quality framing materials.

When all these layers are combined, the cost skyrockets past Monolith, and the assembly is still less durable and more vulnerable to moisture and long-term degradation.

Put simply: matching Monolith’s performance with traditional construction isn’t just difficult — it’s almost always more expensive.

Don’t believe us? Let’s run an official cost comparison for your next build and show you the numbers.

ICF stands for Insulated Concrete Forms, a modern construction system that combines reinforced concrete with insulating foam blocks. These blocks remain in place as part of the structure, providing strength, insulation, and a streamlined building process.

Copyright © 2025 Monolith ICF Empowering Communities, Revolutionizing Construction with Advanced Polyurethane Technology.